Why Signals?

Some days, I wonder why I'm so interested in what is basically a brightly coloured rag sent up a wooden pole, that somehow conveys a lawful order.

The era of naval signals that captivates me the most is that of the Royal Navy from 1799 to 1805. It may seem like a relatively brief period, but it was a time of significant leaps in how the Royal Navy' used flag signals.

For me, it saw the start of a unified approach to Naval flag signals, as up to this time, the meaning of flags could differ depending on the flag officer commanding. Each flag officer would produce their signal books, which were given to vessels under their control.

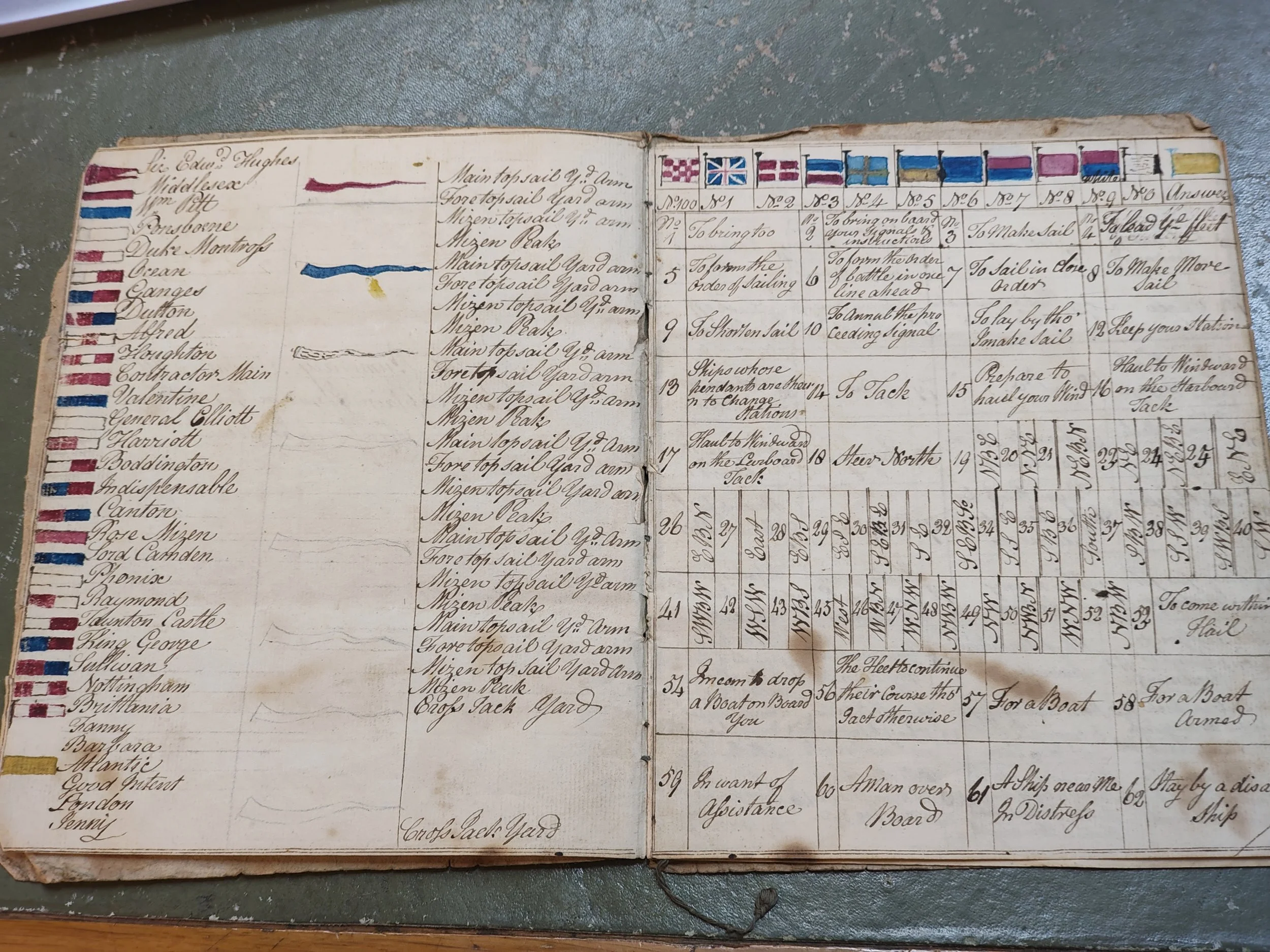

Example of a individual flag officers signals dated 1795

In 1799, the Admiralty introduced a standardised set of signals for ships of war, along with a uniform system of signal flags and pennants across the fleet.

In 1804, upon learning that the signal code book may have fallen into French hands, the Admiral ordered changes to the signal flags to prevent the French from reading British signals. These changes are documented in period signal books.

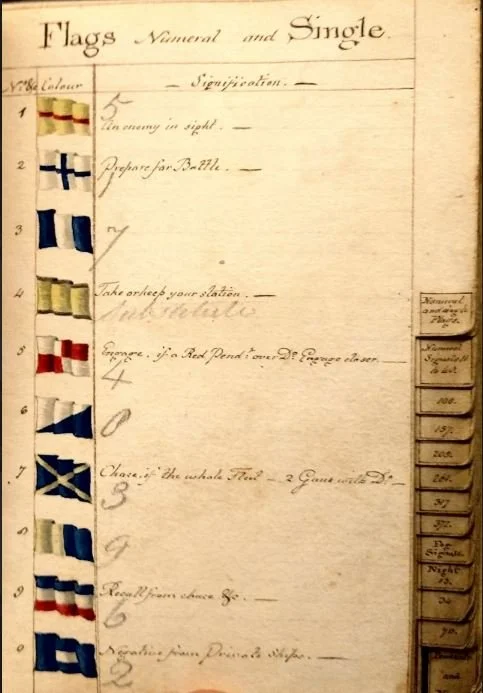

Handdrawn pictures depicting signal flags with pencil numbers showing their number

In 1800, Captain Sir Home Popham published his Telegraphic Signals or Marine Vocabulary, and by 1803, it was adopted by the Royal Navy to supplement the existing basic signal book. His system introduced over 3,000 words and commonly used phrases, each assigned a unique flag code. This was the code used in 1805 by Nelson’s signal officer to send the now-famous message, "England expects that every man will do his duty." That signal, for example, was encoded as: 253, 269, 863, 261, 471, 958, 220, 374, 4, 21, 19, 24.

Reviving The Trafalgar Signal

Picture the Georgian Royal Navy as a far more colourful place, with flags of every hue and enormous ones being hoisted across the fleet. While researching the size of signal flags used during that period, I contacted the National Museum of the Royal Navy in Portsmouth to ask about the dimensions of the flags flown on HMS Victory when Nelson’s signal is hoisted each year on the anniversary of Trafalgar.

Although they didn’t have the information themselves, the team at the National Museum of the Royal Navy helpfully directed me to the Admiralty Library part of the Royal Navy’s Historical Branch and to the Yeoman of the Admiralty (YOTA), who also serves as the Fleet Seamanship Warrant Officer.

A big shout out to Jenny at the Admiralty Library for patiently putting up with my many flag-related questions! She managed to find a note in Flags at Sea by Timothy Wilson (1986), which cites a 1790 Navy Board letter instructing Lord Howe that, on larger ships, signal flags were to be “14 breadths, or about 12 ft broad, 14 ft long,” and on smaller vessels, “about 10 ft broad, 12 ft long.”

Also, thank you to the YOTA, who kindly informed me that the current fleet standard for signal flags is Size 4: 21" × 18" (53 cm × 46 cm).

I still couldn’t find out the exact size of the signal flags currently used on board Victory for the Trafalgar anniversary hoists. With no luck from online sources, I jumped in the car and made the three-hour trip down to Portsmouth to do some on-the-ground research.

Once there, I headed aboard HMS Victory, tracked down a few of the guides, and did my best not to come across as a complete flag nerd with all my questions!

A massive thank-you to James on the Lower Gundeck, and to the duty Royal Navy Quartermaster, who managed to find the answer for me: the flags used for the Trafalgar hoist on board Victory are approximately Size 10: 84" × 60" (213 cm × 152 cm).

Armed with that information, I was finally able to order a couple of signal flags and begin recreating some period correct signal hoists.

The Fleet flagship

The original aim of my project was to hoist Signal 16 from Victory’s mizzen mast—a goal that was kindly supported by the First Sea Lord and his office. Knowing that this small passion project was being discussed at such a high level was a genuinely amazing feeling!

Snippet from the email

Unfortunately, the project wasn’t supported by the National Museum of the Royal Navy at the time, so I once again reached out to the Yeoman of the Admiralty (YOTA) to see if there might be another option. He kindly pointed me towards CPO Adheny down at HMS Collingwood, which—very fittingly—is the Royal Navy’s current school for communication training.

On the 23rd of July, I headed south to Portsmouth to visit Collingwood, where I was given the nickel tour and a fascinating insight into 21st-century fleet communications. The original plan was to hoist the signal on the base’s main mast, but on the day of my visit, it was flying the colours at half-mast—so that plan had to be shelved.

Thankfully, there was a backup plan: to use one of the site’s training masts, which are primarily used by the Royal Fleet Auxiliary (RFA) when training their communications staff. We even bumped into the RFA Commodore, who happened to be visiting a new intake at the time.

We were kindly supported by a group of Royal Navy sailors undergoing their initial communications training, who had to endure a bit of a history lesson from me about the art of signalling. To their credit, they listened with genuine interest!

What struck me most during the visit was that not much has changed since 1803. While terminology and technology have evolved—and light signals and radio are now part of the toolkit—the core principles of naval communication remain remarkably consistent. When I showed the staff Victory’s signal logbook from 1804, its format was almost identical to that of a modern-day signal log. Even the ATP-01 Allied Maritime Tactical Signal and Manoeuvring Book, used across NATO navies today, is, in essence, an evolved version of the original Admiralty and Popham signal books.

Next Steps

This whole voyage has only deepened my passion for the project, so where do I go from here?

I’ve treated myself to a complete set of 15 signal flags from the Flying Colours flag makers, though at a more manageable Size 4. With these in hand, I plan to begin recreating more historic hoists and signals.

Looking ahead, I’d like to build my confidence and begin speaking publicly about this project and the broader history of naval signalling. I genuinely believe it’s essential to pass on this knowledge to keep the subject alive for future generations.

And ultimately? My end goal remains the same:

To hoist the signal from HMS Victory—and, hopefully, from any other vessel that would be kind enough to invite me aboard!

I remain your humble and obedient servant

Beck